Take a moment and imagine this:

A cotton T-shirt, born in a field in India, dyed in a mill in China, stitched in Bangladesh, sold in London, and discarded in Ghana.

That’s the typical life cycle of apparel today — a straight line from resource to waste.

But the world no longer moves in straight lines. Consumers, investors, and even regulators have begun asking: What happens after the last wear?

The truth is simple yet profound — linear supply chains are breaking down in a circular economy.

The End of the One-Way Street

For decades, fashion has been built on a “take-make-dispose” model.

Raw materials come in, products go out, and whatever’s left — scraps, wastewater, unsold inventory — quietly disappears into landfills or incinerators.

It worked when resources seemed infinite and transparency optional.

But in 2025, with EU Due Diligence laws, Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks, and consumers demanding “proof, not promises,” that old one-way street is collapsing.

Supply chains are no longer just about moving goods.

They’re about moving value — circularly, not linearly.

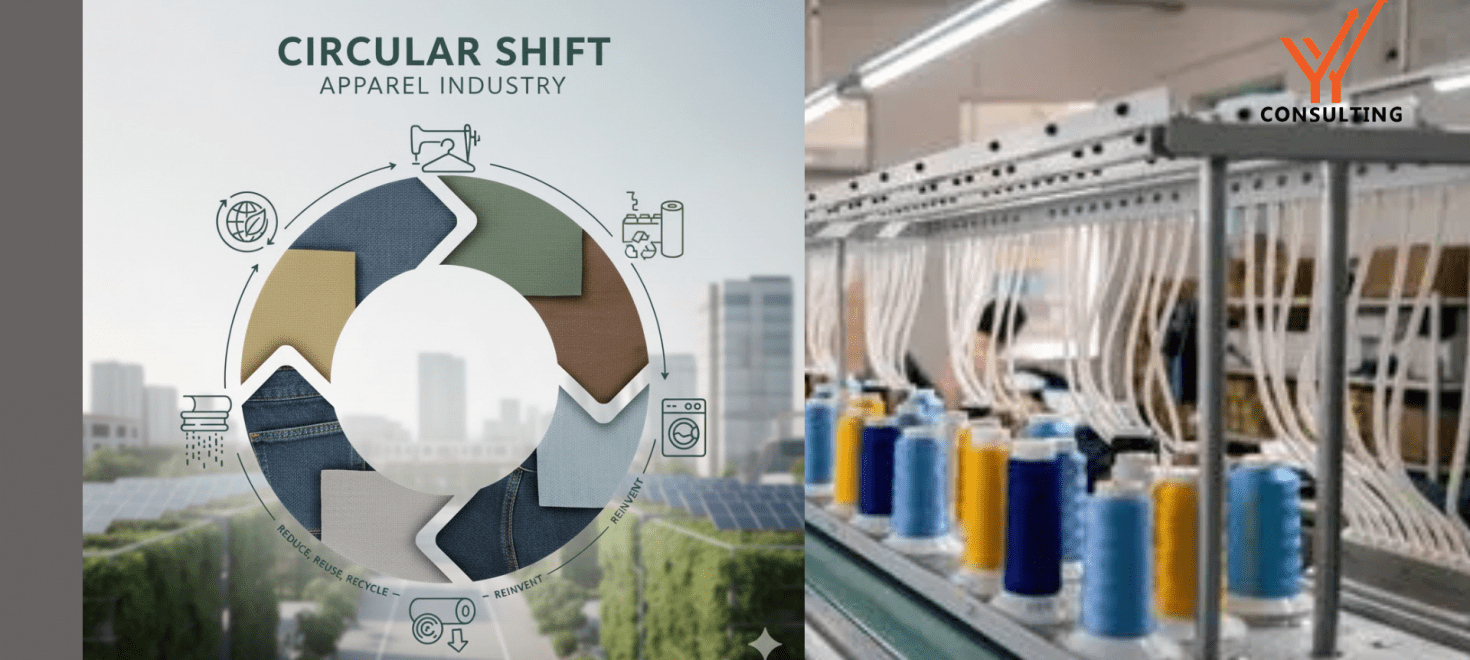

The Circular Shift: From Chain to Web

A linear chain connects producers and consumers in one direction.

A circular network, on the other hand, keeps materials, data, and accountability in motion — continuously looping between fiber producers, garment manufacturers, brands, recyclers, and even consumers themselves.

In the circular world, the product’s end becomes the beginning of something else.

Think of it like this:

- A brand sources organic cotton.

- The cutting floor waste from the factory is collected, re-spun into yarn, and re-used for next season’s capsule collection.

- Post-consumer returns are sorted, fiber-to-fiber recycled, and re-introduced into the material loop.

That’s not fantasy — it’s already happening.

Saitex in Vietnam recycles 98% of its water and reuses fabric waste to make new garments under the brand Rekut.

Renewcell in Sweden turns worn cotton clothes into Circulose — a pulp that replaces virgin cotton or viscose.

Even Levi’s now asks suppliers to track garments beyond sale — a radical shift from the old “ship and forget” mindset.

The Fallacy of the ‘Final Destination’

Traditional supply chains were designed with an endpoint — “shipment done, responsibility over.”

But in a circular economy, there is no final destination.

Every output — whether fabric scraps, reject pieces, or returned items — has a potential second life.

Waste becomes inventory. By-products become business models.

When H&M launched its “Looop” machine, allowing customers to recycle old garments in-store into new ones, it didn’t just create buzz — it rewired expectations.

Suddenly, clothing wasn’t disposable; it was renewable.

The same principle is now cascading into sourcing.

Buyers are asking factories not just what they make, but how they plan to recover, recycle, or regenerate it.

Why Linear Systems Fail in a Circular World

Let’s be brutally honest — linear supply chains are blind.

They don’t know where materials come from, can’t track where they go, and rarely measure what gets wasted.

This opacity breeds three major problems:

- Resource Volatility

As cotton prices swing and polyester faces fossil fuel scrutiny, factories relying solely on virgin inputs are at constant risk. Circular systems, by contrast, create material resilience through reuse. - Compliance Risk

New laws like the EU Textile Strategy and CBAM will require end-to-end traceability.

A linear model simply can’t deliver that — it’s like trying to prove a circle exists with a straight ruler. - Lost Revenue

Every meter of scrap fabric, every returned garment, every unused trim — that’s value leaking out of the system.

Circular manufacturers capture that value back through recycling, resale, or redesign.

In short: the linear model bleeds, while the circular model breathes.

From Supply Chain to Value Network

The future isn’t a chain — it’s a network where collaboration replaces transactions.

In a traditional chain, each link protects its margin.

In a circular network, each participant shares responsibility and benefit — from cotton farmers to recyclers, from dye houses to data platforms.

Here’s how this shift looks in practice:

- Brands become custodians, not just customers.

They co-invest in sustainable raw materials and share data upstream.

Patagonia’s partnership with Recover™ for recycled fibers is a perfect example. - Factories become solution providers.

Instead of only manufacturing garments, they also handle waste segregation, fabric recycling, and take-back logistics.

Sree Santhosh Garments in Tirupur, for instance, now sells cotton waste back to yarn mills — turning scrap into revenue. - Suppliers become storytellers.

With digital IDs, QR codes, and blockchain-enabled traceability, every roll of fabric can now “tell” its own circular story — from fiber source to afterlife.

When each node in the network collaborates, the value multiplies.

The Power of Data in Closing the Loop

Circularity isn’t just about materials — it’s also about information flow.

Imagine a world where a brand knows:

- exactly how much energy went into a fabric,

- what chemicals were used in dyeing,

- how many times the fiber has been recycled, and

- who stitched it last.

That’s not science fiction.

Platforms like TrusTrace, TextileGenesis, and EON are making this visibility real — linking every stage of production with a digital thread.

Factories that embrace these tools are no longer “vendors”; they become data partners — an identity that commands higher trust, longer contracts, and premium pricing.

The irony? The circular revolution isn’t killing manufacturing jobs.

It’s creating new kinds of jobs — data analysts, material recyclers, lifecycle designers — the next generation of apparel professionals who think like engineers and act like environmentalists.

Mindset Before Machinery

Here’s the hard truth:

You can’t bolt circularity onto a linear mindset.

Factories that rush to buy “green” certifications or recycling machines without changing culture often end up in what we call “eco-cosmetic mode.”

They look sustainable on paper but operate the same old way — reactive, fragmented, and short-term.

True circularity starts with leadership that asks new questions:

- Can our offcuts become raw material for someone else?

- Can we redesign products to last longer or be easier to disassemble?

- Can we train workers to separate, sort, and value waste?

One Bangladesh factory we worked with began segregating fabric waste by color and fiber composition, instead of mixing it all. Within three months, they generated a new revenue stream selling sorted waste to recyclers — proof that sustainability and profitability aren’t rivals but partners.

The Economics of Circles

Circularity isn’t charity. It’s smart business.

Let’s look at the math:

- Up to 15% of fabric is wasted during cutting.

- Around 30% of garments produced globally remain unsold.

- Each kilogram of textile waste recycled can offset 3 to 4 kilograms of CO₂ emissions.

Now imagine if even 50% of that waste was monetized through recycling or resale.

That’s not just environmental impact — that’s millions of dollars in recovered value.

Companies like Renewcell, Worn Again Technologies, and Infinited Fiber are already proving that waste-to-fiber innovation can be scalable and profitable.

The future will favor factories that treat circularity as ROI, not PR.

Consumers Are Completing the Circle

Circularity doesn’t end at the factory gate — it extends to the people wearing the clothes.

Gen Z and millennial consumers, who now drive over 60% of global fashion demand, are redefining what “value” means.

They care about provenance, durability, and afterlife — not just aesthetics.

That’s why resale, repair, and rental markets are booming.

Brands like Zara and Decathlon have launched repair programs.

The North Face Renewed and Patagonia Worn Wear are rewriting how customers engage with products.

For factories, this shift means one thing: transparency is no longer optional.

Your data, your design, and your waste management will soon be visible to the final consumer — and that’s both the challenge and the opportunity of this new age.

What Circular Supply Chains Look Like

Here’s what a future-ready apparel supply chain might look like in 2030:

- Design for Disassembly – Every garment designed with clear end-of-life in mind.

- Material Traceability – Digital IDs tracking fibers from farm to finished product.

- Closed-Loop Factories – On-site waste segregation, water recycling, and fabric recovery.

- Collaborative Logistics – Shared transport and reverse logistics to minimize carbon footprint.

- Data-Driven Decisions – AI predicting returns, optimizing reuse, and matching waste to new demand.

This isn’t idealism — it’s evolution.

And factories that start adapting now will lead the transformation, not chase it.

From Compliance to Competitiveness

A circular mindset doesn’t just help meet regulations — it builds resilience.

When supply chains loop, factories need fewer virgin inputs, generate less waste, and build stronger buyer relationships through transparency.

It’s a win-win — for margins, for reputation, and for the planet.

Linear systems treat every order as an end.

Circular systems treat every order as a beginning.

That’s the mental shift defining the next decade of apparel manufacturing.

Closing the Loop: A New Definition of Success

In the 20th century, success in apparel meant bigger factories, faster output, and cheaper costs.

In the 21st century, success will mean smarter systems, transparent loops, and sustainable longevity.

Factories that cling to linearity will soon find themselves out of sync with both markets and morals.

Those that embrace circularity — not as a compliance checklist, but as a core strategy — will redefine leadership in fashion manufacturing.

Because in a world that’s becoming circular, straight lines only lead to dead ends.

Groyyo Consulting partners with factories and brands across Asia to design circular manufacturing ecosystems — integrating material recovery, process transparency, and digital traceability to build the value networks of the future.

Leave a Comment